Optimising the first over

Six games into the 2017 T20 Blast, Kent were the slowest starters in the competition. Even enduring a maiden first over at home to Gloucestershire. In their seventh game, against Somerset, the team switched things up. Joe Denly moved into the opening slot, with his partner, Bell-Drummond replacing him at the other end

Superficially, the switch appeared to work. In the following eight games, Kent were scoring more runs after 3 balls (+0.6), more runs in the first over (+0.5), and more runs in the PowerPlay (+2.6)

These are not big numbers. You might expect a team starting from such a low baseline to make greater improvements from regression to the mean alone. Kent’s first over ranking did improve... but not much. They climbed from worst to second worst for the remainder of the season

These figures also don’t account for the fact that Denly lost his wicket twice in that first over. Neither dismissal was obviously symptomatic of over-aggressive shots but Kent took a risk by entering him into the firing line from the very first ball. Kent’s best batsman was down twice after just a few shots had been fired

These are very small samples. And it would be unreasonable to draw hard conclusions from only a few matches. With Kent often starting games as the perceived underdog, it is defensible to to adopt a high-risk strategy. Risking your best batsmen for a couple of extra early runs certainly fits that description

How important is the first over? It features the lowest run rate, the fewest wickets, and the variance between the best outcomes and the worst is smaller than any other over in a T20 innings. Getting through it unscathed seems like a reasonable objective for the batting side

Predictive models and the conventional wisdom would suggest otherwise. My expected total model is particularly sensitive to first events in the first over. An early four or six can move the needle dramatically. Quick runs would seem to put the batsmen in the driving seat and alleviate pressure

But both the predictive models and he conventional wisdom are biased. This is because the first over also provides information. Before games, the models are unaware of pitch conditions, but clues can be found as soon as the game starts. Just as a pro gambler might react to seeing a new batsman drive cleanly down the ground with their first shot, my models are quickly adjusting expectations based on the earliest data available

The same applies to the casual observer. A speedy start affects their perception of future events as much as it truly sets the tone for the rest of the match

When we analyse the problem more carefully, it becomes clear that runs in the first over aren’t special. Look at three charts below. They show the percentage of times that the team with the superior run total wins, for each of the first three overs. As the size of that run advantage increases, the likelihood that that teams wins also increases

I deliberately neglected to specify which chart corresponds to which of the first three overs*. It doesn’t matter. All the charts are the same. For a particular over, a team that scores 5 runs more than their opponent has a 56% chance of winning the match, regardless of which over we are talking about. A team that scores 8 runs more has a 60% chance. A run is a run is a run

* Green = Over 3 ; Grey = Over 1 ; Purple = Over 2

Back in Kent, neither Denly nor Bell-Drummond has a tendency to score quickly in the first over anyway. Quite the opposite. Per ball, Joe Denly scores 0.4 runs more in the second over than in the first. Much higher than the typical T20 player whose run rate ticks up just 0.2 runs per ball

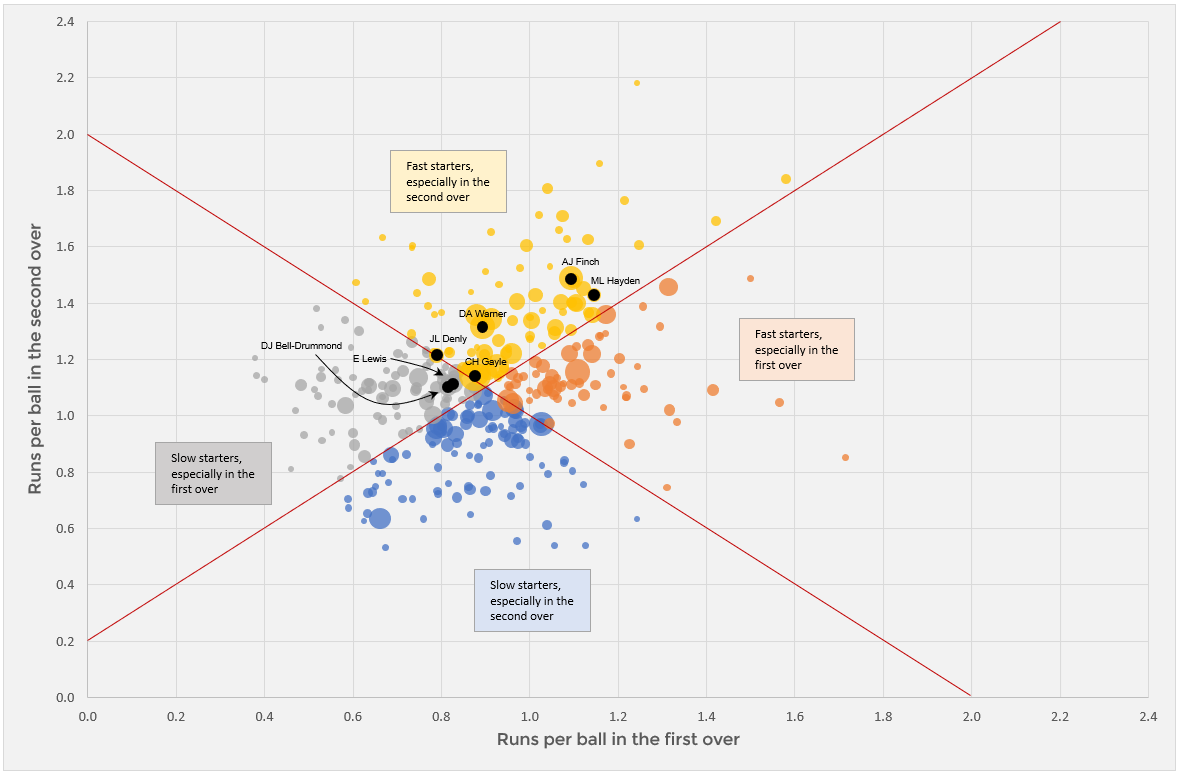

He is in good company. Openers such as Gayle, Finch, Warner, Lewis, Hayden, all start slowly before turning on the blasters. The chart below divides players into four groups based on their run rates in the first and second overs

Each of the four groups has a colour. The yellow group includes players who tend to score quickly, averaging a high strike rate through the first two overs. But they are biased towards the second over. The typical T20 player averages 0.2 runs more per ball in the second than the first. For the yellows, this discrepancy is even larger

The orange group also score quickly but biased towards the first over. The majority of oranges still score slightly more quickly in the second but the difference is not so pronounced. The grey and blue players score slowly. The greys are especially slow in the first over before kicking on. The blues score at a reasonable rate in the first but don’t then accelerate

** Avg. bat value represents the added runs value that the player provides above the average IPL batsman. The numbers are negative because the average IPL batsman is quite good

Once again, it makes very little difference whether you score runs in the first or the second. Whether you open with an orange or a yellow. Or with a blue or a grey. Across the matches analysed, the yellows had a smidgen more runs by the end of the Powerplay but had also lost more wickets

This becomes interesting when you consider the players in each group. The yellow and grey groups contain significantly more valuable players than orange and blue. This makes sense. When you have a player like Warner heading off the innings, you can allow him a few balls to get set. Once he gets going, he’ll catch up for lost time and his wicket is far too valuable to throw away

Yet despite better players, the yellow group barely outpaced the orange - at the end of the Powerplay, they were ahead by about a run but had lost more wickets on average. According to my expected total model which accounts for both runs and wickets, they were actually behind

The situation between the greys and blues is similar: the grey players tend to be significantly more valuable but the differences in outcome are small; if anything the less valuable, blue players come out on top

How to reconcile the fact that all runs are seemingly created equal with the fact that teams tend to fare better with openers who are more biased towards the first over?

Wickets. A run may be a run may be a run. But a wicket isn’t necessarily a wicket isn’t necessarily a wicket, if you’ll excuse the double negative (and clumsy rhetoric). In other words, unlike runs, not all wickets are created equal

Early wickets have an out-sized impact on the outcome of a game. The chart below shows the impact of wickets and sixes, depending on the over. It is immediately apparent that wickets are most valuable early whilst sixes have roughly the same value throughout

We should note that the “new information effect” is still at work here. The predictive models may overstate the impact of an early wicket because it also provides new information about the likely disparity in quality between the two teams

But there are strong reasons to believe that the decline is real. Most importantly, early wickets tend to send home the best batsmen. David Warner's wicket is a coveted commodity. He can take as many balls as he needs to ensure he doesn’t suffer an early exit because we know how valuable it is to have him at the crease. Potentially, the reason that the lower-ranked blues and oranges were able to keep up is because they are lower ranked. They could keep pace in the early overs knowing that their wicket is less crucial to the final result

This isn’t an entirely fair characterisation. For one thing, the higher-ranked yellows actually lost the most wickets during the Powerplay, not the oranges

But the evidence is starting to form a coherent picture: Runs are valuable whenever they come but they are hardest to acquire in the first over. Early wickets are valuable but only because they represent the biggest scalps. Strong players who start slowly do so to ensure that they don't succumb to unpredictable pitch conditions

For some, this may seem like a lot of words and analytics to reach a position they already hold: some teams should open the batting with less valuable players who can nonetheless accumulate runs just as quickly as more traditional openers. Indeed, we have a specific term for these players: pinch hitters. The word has evolved slightly over time but here I am talking specifically about promoting a player who normally bats at eight or lower to the top of the order with explicit instructions to smash the hell out of the ball

Sunil Narine (orange) is the most obvious example. In addition to being an outstanding bowler, Narine offers his teams free runs at the top of the order. I have written about his value to the Kolkata Knight Riders in extensive detail (as have several others). And other teams are starting to follow suit - Shahid Afridi and Mitch McClenaghan have also played the position in recent years

Joe Denly was perhaps the wrong choice for Kent – Matt Coles may have been the better choice. His strike rate is decent (135) and he deals in boundaries: his shots have a 10% chance of finding the ropes and a 7% chance of clearing them. He also has a terrible average… which in this case is a good thing!

As always, context is everything. In the same way that the decision to employ a first over specialist depends on match-ups with the opening batsmen – so does pinch hitting. Matt Coles tends to struggle against left -arm pace bowlers; teams who favour right-arms or spinners would be better targets

Venue matters too. My sample sizes are a small, but the evidence suggests (and logic would agree) that for flat pitches, maximising runs should take precedent. In these situations, players like Warner need as much time as possible to take advantage of field restrictions

Most teams can plan easily for the first over without needing to consider a range of possible scenarios. The batting teams knows who will face the first ball. And they can be 67% certain that the same player will face the next one too. They may also be able to predict who is going to open the bowling against him

An undervalued element of T20 batting strategy is variance and unpredictability. In The Theory of Poker, David Sklansky repeats, repeatedly, that a poker player wins every single time their opponent makes a wrong decision; a decision that they would not have made if they could see every hand

One of the reasons that specialist first-over bowlers are more common than pinch hitters is that the bowling team knows who will open. They can see their opponent’s hand. But that doesn’t mean you can’t make their lives more difficult. Introducing flexibility into the batting line-up makes a team harder to prepare for. The bowling team still have the advantage but pre-match scenario planning becomes that extra bit more difficult. Within the game, they are more likely to make sub-optimal decisions. And when that happens, just like in poker, you win